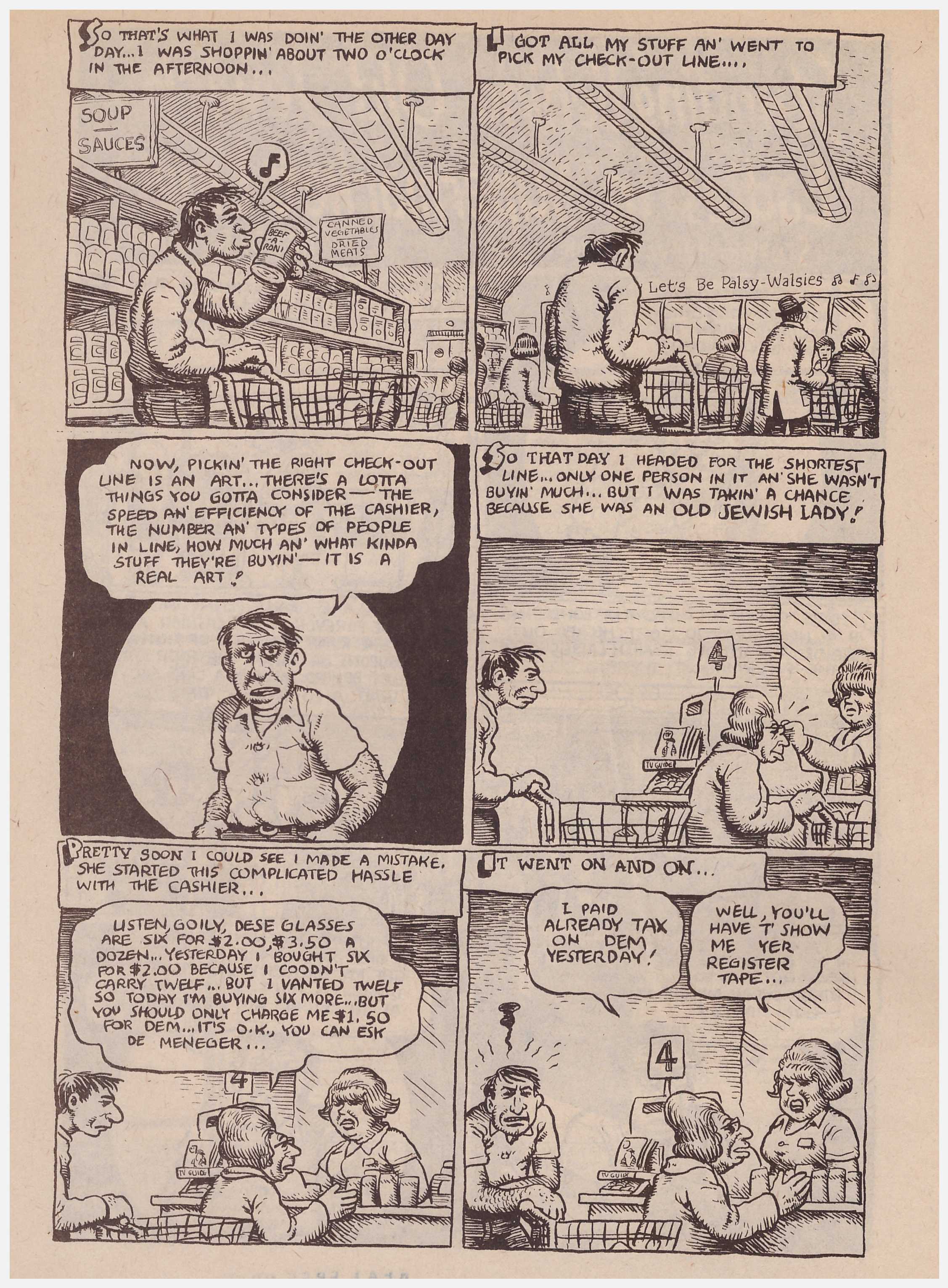

For a new wave of “alternative” comics artists, Pekar’s work championed an influential mode of autobiography that privileged the quotidian over the epochal, the mundane over the traumatic. The results are sometimes inconsistent, but Pekar’s emphasis on straightforward presentation in both text and image was influential to a post-underground generation seeking contemporary models in opposition to genre-based commercial comics. Unlike work by other comics writers who intensely directed their collaborators toward precise visual compositions – such as Harvey Kurtzman and Alan Moore – Pekar’s stories tend to more visibly bear the stamps of his illustrators. Pekar preferred to work with available (and affordable) artists who conformed to his vision of a restrained, literal, representational comics art. Although he found a valuable collaborator in Crumb, Pekar’s overall choice of illustrators largely suggested a reaction to the metaphorical visuals, cartoon languages, and stylistic flourishes exhibited in dazzling variety by the underground cartoonists who preceded him. Pekar was also unusual as a writer working as an auteur in a visual art form. With no clear audience, American Splendor balanced understated incidents with Pekar’s street-corner-philosopher’s perspective on life. Pekar’s major subjects were, instead, the forgotten moments and ignored people he noted daily as an autodidact file clerk living in Cleveland, as well as his own verbose, cantankerous, opinionated self. Pekar, 37 at the time, recognized the possibilities that work like Crumb’s represented, but had felt alienated from the psychedelicized ethos and lifestyle of the counterculture. As a self-published black-and-white comic book dealing with adult themes, it was as much a reaction to as an extension of an underground publishing scene that was rapidly dissipating. Pekar’s American Splendor series, launched in 1976, was an unlikely project. Green’s work inspired many others, including Art Spiegelman and Aline Kominsky-Crumb, to explore autobiographical comics before the underground comix milieu wound down in the mid-1970s. And even Crumb has acknowledged the galvanizing influence of Justin Green’s seminal 1972 comic book Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, a dense and deeply symbolic account of the author’s experiences with Catholic guilt, obsessive compulsive disorder, and hallucinatory sexual dysfunction. Robert Crumb, the illustrator of some of Pekar’s most memorable works, took the self as a subject in several of his own early underground comix. In the American comics tradition alone, the pioneering female cartoonist Fay King regularly inserted herself as a character in her Jazz Age cartoons and comic strips.

Harvey Pekar did not invent autobiographical comics.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)